While many factors make up human self-identity, most Americans agree the primary factor that makes up their identity is family. Nearly two-thirds of Americans say their family makes up “a lot” of their personal identity (62%).

In a recent study, Barna Group asked adults how much a variety of factors influences their personal identity. While it may not come as a surprise that “family” ranks first, it is perhaps unexpected how much more likely certain groups (Elders, practicing Christians, residents of the Midwest) are to say so and how much less likely other groups (Millennials, people with no faith, residents of the West) are to point to family as a key part of their identity.

What other factors do adults consider central to their identity? And how do faith, age, politics and even area of the country affect people’s self-perceptions?

Faith Leadership in a Divided Culture

The Religious Freedom Debates - and Why They Matter to All of Us

Family, Country, God

“God, family, country” might be the oft-touted creed of country music, but most Americans scramble the order. Adults are most likely to point to their family as making up a significant part of their personal identity, “being an American” comes second and “religious faith” is in third. In a tie for a distant fourth are people’s career and their ethnic group. Significantly fewer adults would claim their state or their city have much impact on their personal identity.

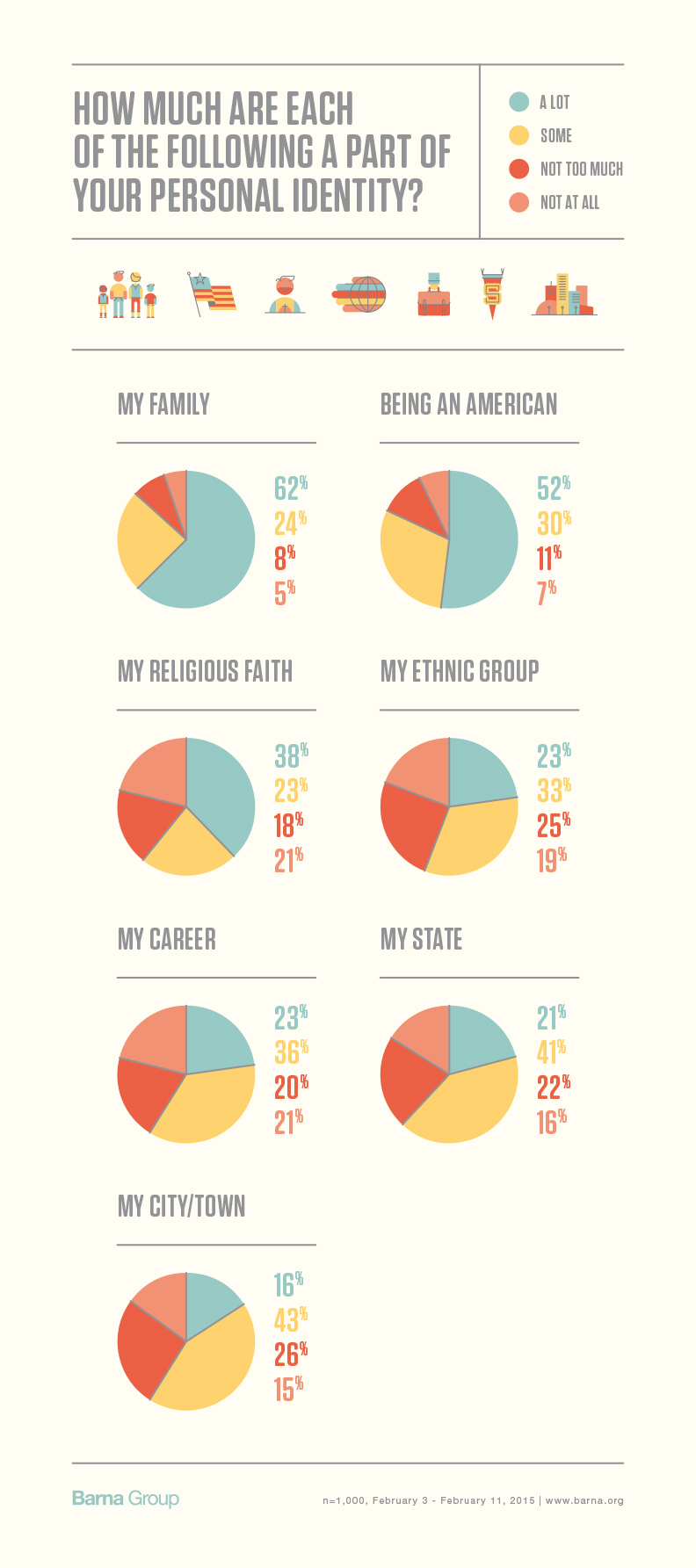

When asked how much each of the factors make up their personal identity—“a lot,” “some,” “not too much” or “not at all”—nearly two-thirds say their family makes up a lot of their personal identity (62%).

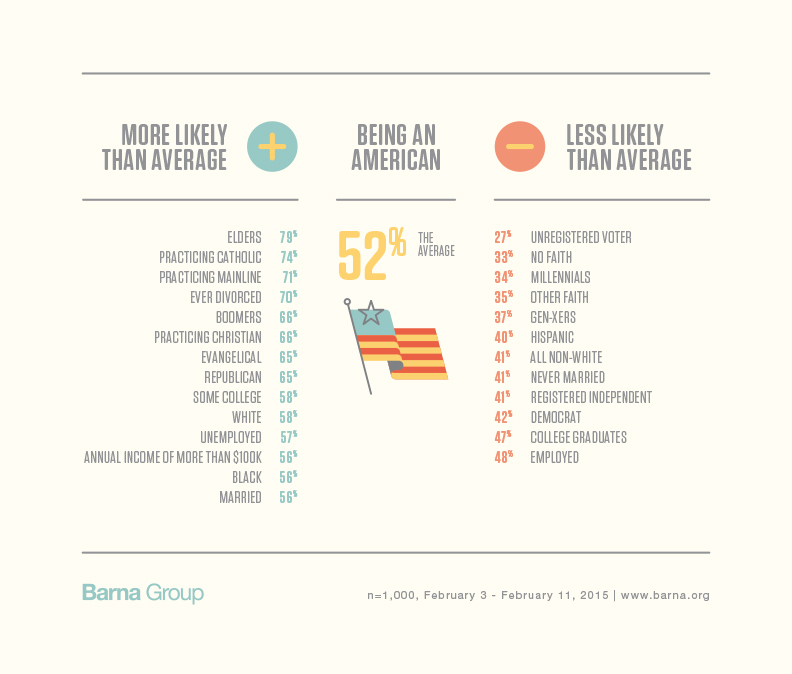

Patriotism still runs strong in most Americans: More than half of all adults say being an American makes up a lot of their personal identity (52%).

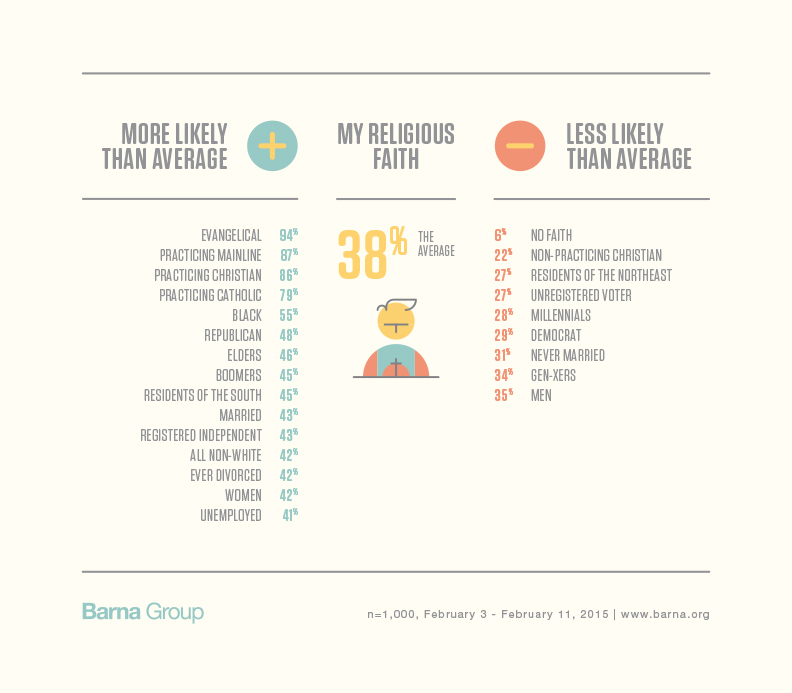

While religious faith squeaks into the top three, there is a sharp drop from the first two factors in the number of Americans who say their faith is a major part of their identity. A majority of Americans agree their family and their country are central aspects of who they are, fewer than two out of five adults say their religious faith makes up a lot of their personal identity (38%). About the same proportion of adults give little or no credence to the idea that faith is part of their identity: 18 percent say faith doesn’t make up much of their identity and one in five say it doesn’t affect their identity at all.

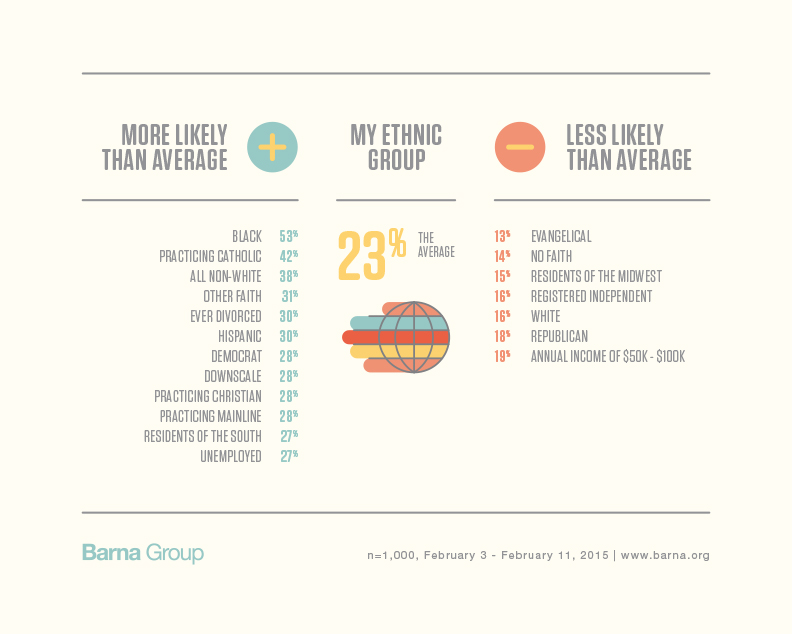

Most Americans seem to agree with the familiar maxim that what you do is not who you are: Less than one-quarter of adults say their career makes up a lot of their personal identity (23%), though more than a third admit their career makes up some of their personal identity (36%). Similar percentages point to their ethnic group as shaping their identity: Just under a quarter (23%) say it makes up a lot of their identity.

Hometown and state pride might spike during football and basketball seasons, but in general Americans don’t believe their state or their city significantly affects their personal identity. Only one in five Americans say their state makes up a lot of their personal identity (21%) and even fewer say their city or town does (16%). However, more than two out of five—more than for any of the other factors—admit their locale has at least some impact on their personal identity: 41% say their state makes up some of their identity and 43% say their city does. In other words, geography is not a predominant aspect of self-identity, but it plays a surprisingly important part in the background for most adults.

Generational Identities

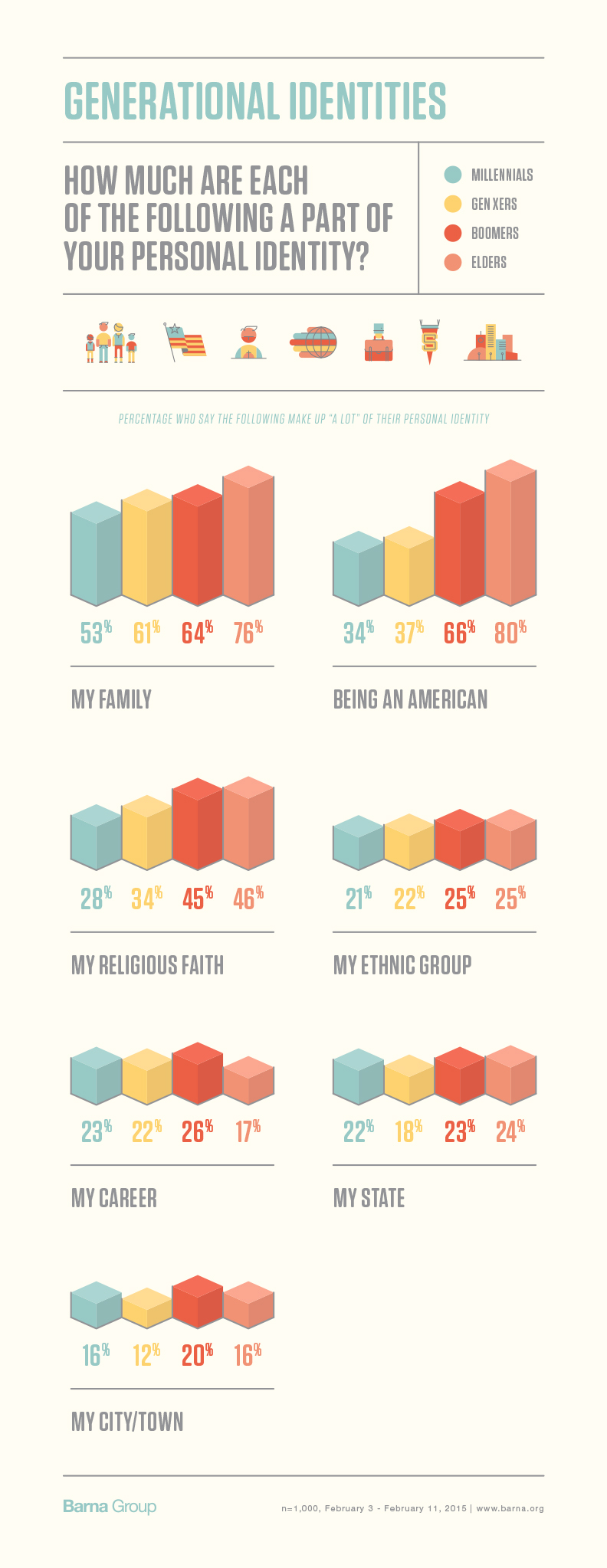

When it comes to identifying as an American, there is nearly a 50-point drop between the oldest generation—Elders—and the youngest. Four out of five Elders say that being an American makes up a lot of their personal identity, but only one-third of Millennials say the same (34%). While there is a significant drop between each generation and the next, the sharpest decline is between Boomers and Gen-Xers. The generation that came of age during Watergate and the turbulent Vietnam War era still says, on the whole, that being an American makes up a lot of their identity (66%). But their children—the generation of globalization, MTV, and the Monica Lewinsky scandal—are far less inclined to claim it as a significant factor: Only 37 percent of Gen-Xers say being an American makes up a lot of their personal identity.

Patriotism is not the only institution that has less of an impact on younger generations. Gen-Xers and Millennials are significantly less likely than their older counterparts to claim any of the factors make up a lot of their personal identity. The exception is career: 23 percent of Millennials, 22 percent of Gen-Xers and 25 percent of Boomers say their career makes up a lot of their personal identity. Only 17% of Elders, who are primarily retired from the workforce, say so.

The most dramatic differences, after patriotism, are family and faith. While Millennials, like most adults, identify more with family than any other factor—53 percent say family makes up a lot of their personal identity—they are still well behind any other generation in feeling this way. Even Gen-Xers, typically much closer to Millennials in their answers, are more likely than Millennials to connect family to their identity (61%). This may be the result of more Gen-Xers than Millennials having started families of their own.

Your Leadership Toolkit

Strengthen your message, train your team and grow your church with cultural insights and practical resources, all in one place.

Identity Politics

Age is not the only divide. For each of the factors surveyed, there are significant gaps along religious, socioeconomic, political and even regional lines.

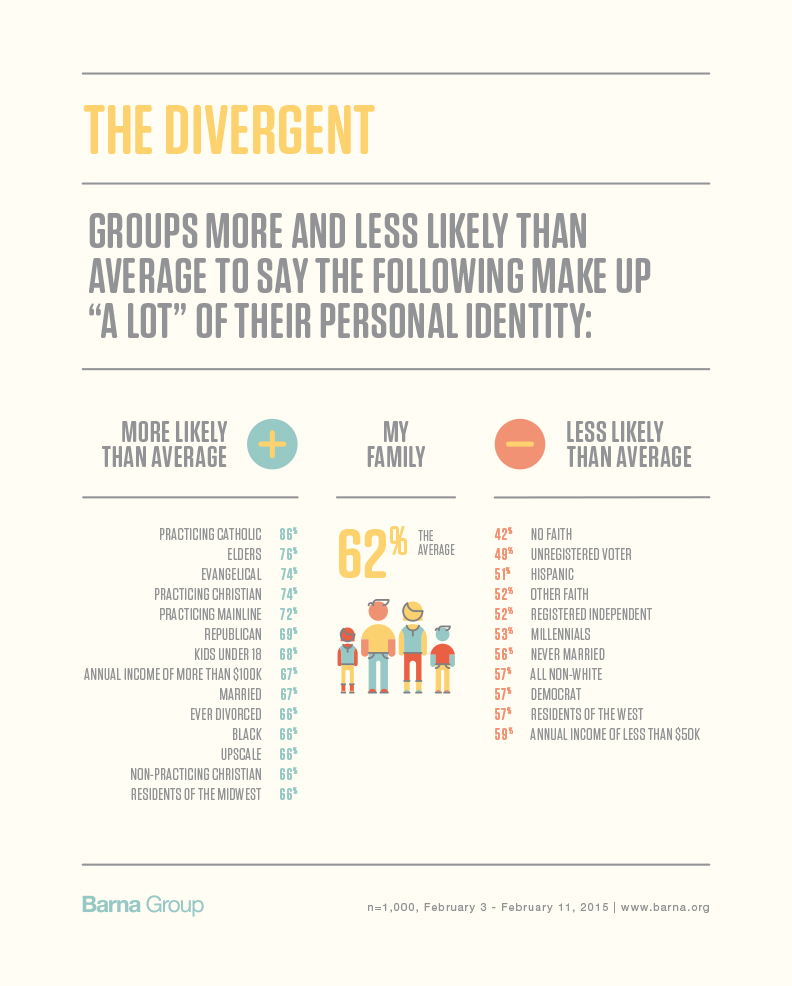

When it comes to naming family as a primary influence on personal identity, those more likely than average to do so include Elders, those of various religious faiths, Republicans, those with families of their own (married adults, adults with kids under 18), Black adults, upscale Americans and residents of the Midwest. Those less likely to do so include adults with no faith, unregistered and Independent voters, Hispanics, those who have never been married, Millennials and Democrats.

Conflating personal identity with “being an American” is the factor on which various groups most significantly diverge. Once again, institutionally minded groups such as evangelicals, Elders and married people are more likely to do so, while unregistered voters, registered Independent voters and those with no faith are less likely. In what will be of particular interest to political parties, Republicans are much more likely than average to say being an American is central to their identity (65% compared to 52% of the general population), while Democrats are less likely than average to do so (42%).

There are few surprises in terms of who highlights religious faith as essential to their identity. Practicing Protestants of all denominations are significantly more likely than the general population to say faith is central to their identity; in fact, aside from practicing Catholics, these groups are all more likely to say their faith, more than any other factor surveyed, makes up a lot of their identity. Practicing Catholics are more likely to say family makes up a lot of their identity (86%) than to say their religious faith does (79%).

Of course, those with no faith are least likely to say religious faith makes up a lot of their personal identity (6%)—and residents of the Northeast (where a larger proportion of non-religious people live) are also less likely (27%). Conversely, residents of the South (the “Bible Belt”) are more likely than average to say faith makes up a lot of their identity (45%). Black Americans, Republicans and women are also more likely than average, while Democrats and men are less likely.

It is worth noting that non-practicing Christians are the second-least-likely group, behind those with no faith, to say faith makes up a lot of their personal identity (22%).

When it comes to those who say their ethnic group makes up a lot of their personal identity, Black Americans, Hispanic Americans and other non-white groups are the most likely to say so. Similarly, other segments that tend to have higher numbers of ethnic minorities—Catholics, Democrats, practicing Christians and mainline Christians—are more likely to say so. Downscale and unemployed Americans are also more likely than average to say their personal identity is closely tied to their ethnic identity, while those with mid-range incomes are less likely—further evidence that economic hardships such as unemployment and underemployment disproportionately affect minority communities.

What the Research Means

“For many people, these numbers will confirm ideas they already had about various groups,” says Roxanne Stone, a vice president at Barna Group and the designer and analyst on the study. “However, there are some themes of disconnection that are worth paying attention to. Younger generations—Gen-Xers and Millennials—are generally less trusting of institutions than older generations. This disenfranchisement holds true in their relative reluctance to claim any of these factors as part of their identity. It is also true that Gen-Xers and Millennials have a reputation for wanting to be individualists—for wanting to break away from traditional cultural narratives and to resist being ‘boxed in’ by what they perceive as limiting expectations. Of course, it will be interesting to see if, as they age, these groups begin to gravitate toward their own institutions and grounding narratives.

“The opportunity, then, for those who hope to reach these younger generations, is to ask where these groups are finding their sense of identity,” continues Stone. “If these traditional institutions and relationships are not as defining for them, what most impacts their identity? Their friendships? Their lifestyle? Technology or entertainment? The media they consume? While Gen-Xers and Millennials might resist being defined by anything, their identities are certainly impacted and shaped by external forces. Recognizing those forces and the impact they have—for better and worse—on their identity will help young adults make decisions about what and where they want to give allegiance.

“In addition to this generational trend of disenfranchisement, Barna has reported on the growing number of unchurched Americans. Much of this group is reflected in the ‘non-practicing Christians’ segment of the population: people who self-identify as Christian but for whom faith and church are not priorities. This group represents a massive slice of the adult population, and their reticence to claim religious faith as a central part of their identity is in line with their general tendency to distance themselves from institutional forms of Christianity. However, the fact that these Americans claim a Christian faith yet are the second least likely group to say faith makes up a lot of their personal identity, should certainly come as an alarming indicator to Christian leaders. This is a group that, as a whole, does not appear to be moving closer to the church or to Jesus.”

Comment on this research and follow our work:

Twitter: @davidkinnaman | @roxyleestone | @barnagroup

Facebook: Barna Group

About the Research

This research contains data from a study conducted among 1,000 U.S. adults conducted online from February 3 to February 11, 2015. The estimated maximum sampling error for this study is plus or minus 3.1 percentage points at the 95 percent confidence level.

Millennials are the generation born between 1984 and 2002; Gen-Xers, between 1965 and 1983; Boomers, between 1946 and 1964; and Elders, in 1945 or earlier. People are identified as having a “practicing” faith if they have attended a church service in the past month and say their religious faith is very important in their life.

“Evangelicals” are defined in this survey as people who meet nine belief conditions. These include saying they have made “a personal commitment to Jesus Christ that is still important in their life today,” that their faith is very important in their life today; believing that when they die they will go to Heaven because they have confessed their sins and accepted Jesus Christ as their Savior; believing they have a personal responsibility to share their religious beliefs about Christ with non-Christians; believing that Satan exists; believing that eternal salvation is possible only through grace, not works; believing that Jesus Christ lived a sinless life on earth; asserting that the Bible is accurate in all the principles it teaches; and describing God as the all-knowing, all-powerful, perfect deity who created the universe and still rules it today. Being classified as an evangelical is not dependent on church attendance, the denominational affiliation of the church attended or self-identification. Respondents were not asked to describe themselves as “evangelical.”

The study relied on a research panel called KnowledgePanel®, created and maintained by Knowledge Networks. It is a probability-based online non-volunteer access panel. Panel members are recruited using a statistically valid sampling method with a published sample frame of residential addresses that covers approximately 97 percent of US households. Sampled non-Internet households, when recruited, are provided a netbook computer and free Internet services so they may participate as online panel members. KnowledgePanel consists of about 50,000 adult members (ages 18 and older) and includes persons living in cell-only households.

© Barna Group, 2015.

About Barna

Since 1984, Barna Group has conducted more than two million interviews over the course of thousands of studies and has become a go-to source for insights about faith, culture, leadership, vocation and generations. Barna is a private, non-partisan, for-profit organization.

Related Posts

How Young Adults in Digital Babylon View the Gospel

- Generations

- Technology

-

From the Archives

Competing Worldviews Influence Today’s Christians

- Culture

-

From the Archives

A Biblical Worldview Has a Radical Effect on a Person’s Life

- Culture

- Faith

-

From the Archives

Religious Beliefs Have Greatest Influence on Voting Decisions

- Culture

-

From the Archives

Meet the “Spiritual but Not Religious”

- Culture

- Faith

-

From the Archives

Did 2020 Shift Americans’ Perceptions of U.S. History?

- Culture

- Faith

Lead with Insight

Strengthen your message, train your team and grow your church with cultural insights and practical resources, all in one place.

Get Barna in Your Inbox

Subscribe to Barna’s free newsletters for the latest data and insights to navigate today’s most complex issues.